PLEASE NOTE ALL THE INFORMATION ABOVE IS FROM THE NHS WEBSITE.

Showing all 6 results

-

Sold By - British Chemist

Betamethasone with Neomycin Cream

£49.99 – £94.99 inc. VAT Learn More -

Sold By - British Chemist

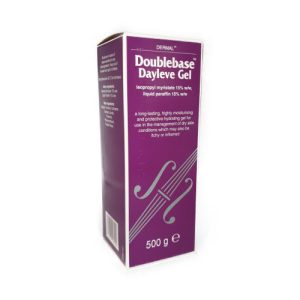

Doublebase Dayleve Gel (100g-500g)

£8.99 – £17.99 inc. VAT Learn More -

Sold By - British Chemist

Hydromol Ointment

£24.99 inc. VAT Learn More -

Sold By - British Chemist

QV Bath Oil

£15.99 – £41.99 inc. VAT Learn More -

Sold By - British Chemist

Dermol 500

£15.99 – £49.99 inc. VAT Learn More -

Sold By - British Chemist

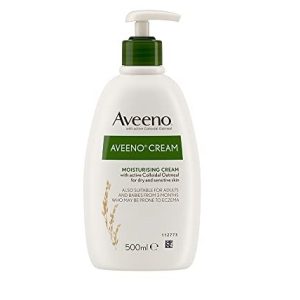

Aveeno Cream

£7.99 – £25.99 inc. VAT Learn More

Information:

Coronavirus advice

Get advice about coronavirus and eczema from the National Eczema Society

Symptoms of atopic eczema

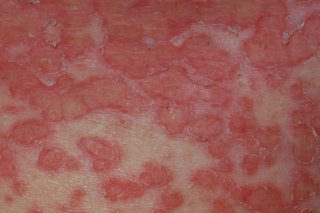

Atopic eczema causes the skin to become itchy, dry, cracked and sore.

Some people only have small patches of dry skin, but others may experience widespread inflamed skin all over the body.

Inflamed skin can become red on lighter skin, and darker brown, purple or grey on darker skin. This can also be more difficult to see on darker skin.

Although atopic eczema can affect any part of the body, it most often affects the hands, insides of the elbows, backs of the knees and the face and scalp in children.

People with atopic eczema usually have periods when symptoms are less noticeable, as well as periods when symptoms become more severe (flare-ups).

When to seek medical advice

See a GP if you have symptoms of atopic eczema. They’ll usually be able to diagnose atopic eczema by looking at your skin and asking questions, such as:

- whether the rash is itchy and where it appears

- when the symptoms first began

- whether it comes and goes over time

- whether there’s a history of atopic eczema in your family

- whether you have any other conditions, such as allergies or asthma

- whether something in your diet or lifestyle may be contributing to your symptoms

Typically, to be diagnosed with atopic eczema you should have had an itchy skin condition in the last 12 months and 3 or more of the following:

- visibly irritated red skin in the creases of your skin – such as the insides of your elbows or behind your knees (or on the cheeks, outsides of elbows, or fronts of the knees in children aged 18 months or under) at the time of examination by a health professional

- a history of skin irritation occurring in the same areas mentioned above

- generally dry skin in the last 12 months

- a history of asthma or hay fever – children under 4 must have an immediate relative, such as a parent, brother or sister, who has 1 of these conditions

- the condition started before the age of 2 (this does not apply to children under the age of 4)

Causes of atopic eczema

The exact cause of atopic eczema is unknown, but it’s clear it is not down to one single thing.

Atopic eczema often occurs in people who get allergies. “Atopic” means sensitivity to allergens.

It can run in families, and often develops alongside other conditions, such as asthma and hay fever.

The symptoms of atopic eczema often have certain triggers, such as soaps, detergents, stress and the weather.

Sometimes food allergies can play a part, especially in young children with severe eczema.

You may be asked to keep a food diary to try to determine whether a specific food makes your symptoms worse.

Allergy tests are not usually needed, although they’re sometimes helpful in identifying whether a food allergy may be triggering symptoms.

Treating atopic eczema

Treatment for atopic eczema can help to relieve the symptoms and many cases improve over time.

But there’s currently no cure and severe eczema often has a significant impact on daily life, which may be difficult to cope with physically and mentally.

There’s also an increased risk of skin infections.

Many different treatments can be used to control symptoms and manage eczema, including:

- self-care techniques, such as reducing scratching and avoiding triggers

- emollients (moisturising treatments) – used on a daily basis for dry skin

- topical corticosteroids – used to reduce swelling, redness and itching during flare-ups

Other types of eczema

Eczema is the name for a group of skin conditions that cause dry, irritated skin.

Other types of eczema include:

- discoid eczema – a type of eczema that occurs in circular or oval patches on the skin

- contact dermatitis – a type of eczema that occurs when the body comes into contact with a particular substance

- varicose eczema – a type of eczema that most often affects the lower legs and is caused by problems with the flow of blood through the leg veins

- seborrhoeic eczema – a type of eczema where red, scaly patches develop on the sides of the nose, eyebrows, ears and scalp

- dyshidrotic eczema (pompholyx) – a type of eczema that causes tiny blisters to erupt across the palms of the hands

The severity of atopic eczema can vary a lot from person to person. People with mild eczema may only have small areas of dry skin that are occasionally itchy. In more severe cases, atopic eczema can cause widespread inflamed skin all over the body and constant itching.

Inflamed skin can become red on lighter skin, and darker brown, purple or grey on darker skin. This can also be more difficult to see on darker skin.

Scratching can disrupt your sleep, make your skin bleed, and cause secondary infections. It can also make itching worse, and a cycle of itching and regular scratching may develop. This can lead to sleepless nights and difficulty concentrating at school or work.

Areas of skin affected by eczema may also turn temporarily darker or lighter after the condition has improved. This is more noticeable in people with darker skin. It’s not a result of scarring or a side effect of steroid creams, but more of a “footprint” of old inflammation and eventually skin tone returns to its normal colour.

Signs of an infection

Occasionally, areas of skin affected by atopic eczema can become infected. Signs of an infection can include:

- your eczema getting a lot worse

- fluid oozing from the skin

- a yellow crust on the skin surface or small yellowish-white spots appearing in the eczema

- the skin becoming swollen and sore

- feeling hot and shivery and generally feeling unwell

See a doctor as soon as possible if you think your or your child’s skin may have become infected.

Read more about infections and other complications of atopic eczema

Atopic eczema is not infectious, so it cannot be passed on through close contact.

Eczema triggers

There are a number of things that may trigger your eczema symptoms. These can vary from person to person.

Common triggers include:

- irritants – such as soaps and detergents, including shampoo, washing-up liquid and bubble bath

- environmental factors or allergens – such as cold and dry weather, dampness, and more specific things such as house dust mites, pet fur, pollen and moulds

- food allergies – such as allergies to cows’ milk, eggs, peanuts, soya or wheat

- certain materials worn next to the skin – such as wool and synthetic fabrics

- hormonal changes – women may find their symptoms get worse in the days before their period or during pregnancy

- skin infections

Some people also report their symptoms get worse when the air is dry or dusty, or when they are stressed, sweaty, or too hot or too cold.

If you’re diagnosed with atopic eczema, a GP will work with you to try to identify any triggers for your symptoms.

- emollients (moisturisers) – used every day to stop the skin becoming dry

- topical corticosteroids – creams and ointments used to reduce swelling and redness during flare-ups

Other treatments include:

- topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus for eczema in sensitive sites not responding to simpler treatment

- antihistamines for severe itching

- bandages or special body suits to allow the body to heal underneath

- more powerful treatments offered by a dermatologist (skin specialist)

The various treatments for atopic eczema are outlined on this page.

Self care

As well as the treatments mentioned above, there are things you can do yourself to help ease your symptoms and prevent further problems.

Try to reduce the damage from scratching

Eczema is often itchy, and it can be very tempting to scratch the affected areas of skin.

But scratching usually damages the skin, which can itself cause more eczema to occur.

The skin eventually thickens into leathery areas as a result of chronic scratching.

Deep scratching also causes bleeding and increases the risk of your skin becoming infected or scarred.

Try to reduce scratching whenever possible. You could try gently rubbing your skin with your fingers instead.

If your baby has atopic eczema, anti-scratch mittens may stop them scratching their skin.

Keep your nails short and clean to minimise damage to the skin from unintentional scratching.

Keep your skin covered with light clothing to reduce damage from habitual scratching.

Avoid triggers

A GP will work with you to establish what might trigger the eczema flare-ups, although it may get better or worse for no obvious reason.

Once you know your triggers, you can try to avoid them.

For example:

- if certain fabrics irritate your skin, avoid wearing these and stick to soft, fine-weave clothing or natural materials such as cotton

- if heat aggravates your eczema, keep the rooms in your home cool, especially the bedroom

- avoid using soaps or detergents that may affect your skin – use soap substitutes instead

Although some people with eczema are allergic to house dust mites, trying to rid your home of them is not recommended as it can be difficult and there’s no clear evidence that it helps.

Read more about preventing allergies

Dietary changes

Some foods, such as eggs and cows’ milk, can trigger eczema symptoms.

But you should not make significant changes to your diet without first speaking to a GP.

It may not be healthy to cut these foods from your diet, especially in young children who need the calcium, calories and protein from these foods.

If a GP suspects a food allergy, you may be referred to a dietitian (a specialist in diet and nutrition).

They can help to work out a way to avoid the food you’re allergic to while ensuring you still get all the nutrition you need.

Alternatively, you may be referred to a hospital specialist, such as an immunologist, dermatologist or paediatrician.

If you’re breastfeeding a baby with atopic eczema, get medical advice before making any changes to your regular diet.

Emollients

Emollients are moisturising treatments applied directly to the skin to reduce water loss and cover it with a protective film.

They’re often used to help manage dry or scaly skin conditions, such as atopic eczema.

In addition to making the skin feel less dry, they may also have a mild anti-inflammatory role and can help reduce the number of flare-ups you have.

If you have mild eczema, talk to a pharmacist for advice on emollients. If you have moderate or severe eczema, talk to a GP.

Choosing an emollient

Several different emollients are available. Talk to a pharmacist for advice on which emollient to use. You may need to try a few to find one that works for you.

You may also be advised to use a mix of emollients, such as:

- an ointment for very dry skin

- a cream or lotion for less dry skin

- an emollient to use instead of soap

- an emollient to use on your face and hands, and a different one to use on your body

The difference between lotions, creams and ointments is the amount of oil they contain.

Ointments contain the most oil so they can be quite greasy, but are the most effective at keeping moisture in the skin.

Lotions contain the least amount of oil so are not greasy, but can be less effective. Creams are somewhere in between.

If you have been using a particular emollient for some time, it may eventually become less effective or may start to irritate your skin.

If this is the case, you may find another product suits you better. You can speak to a pharmacist about other options.

The best emollient is the one you feel happy using every day.

How to use emollients

Use your emollient all the time, even if you’re not experiencing symptoms.

Many people find it helpful to keep separate supplies of emollients at work or school, or a tub in the bathroom and one in a living area.

To apply the emollient:

- use a large amount

- do not rub it in – smooth it into the skin in the same direction the hair grows

- after a bath or shower, gently pat the skin dry and apply the emollient while the skin is still moist to keep the moisture in

You should use an emollient at least twice a day if you can, or more often if you have very dry skin.

During a flare-up, apply generous amounts of emollient more frequently, but remember to treat inflamed skin with a topical corticosteroid as emollients used on their own are not enough to control it.

Do not put your fingers into an emollient pot – use a spoon or pump dispenser instead, as this reduces the risk of infection. And never share your emollient with other people.

Topical corticosteroids

If your skin is sore and inflamed, a GP may prescribe a topical corticosteroid (applied directly to your skin), which can reduce the inflammation within a few days.

Topical corticosteroids can be prescribed in different strengths, depending on the severity of your atopic eczema and the areas of skin affected.

They can be:

- very mild (such as hydrocortisone)

- moderate (such as betamethasone valerate and clobetasone butyrate)

- strong (such as a higher dose of betamethasone valerate and betamethasone diproprionate)

- very strong (such as clobetasol proprionate and diflucortolone valterate)

If you need to use corticosteroids frequently, see a GP regularly so they can check the treatment is working effectively and you’re using the right amount.

How to use topical corticosteroids

Do not be afraid to apply the treatment to affected areas to control your eczema.

Unless instructed otherwise by a doctor, follow the directions on the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

This will give details of how much to apply.

Most people only have to apply it once a day as there’s no evidence there’s any benefit to applying it more often.

When using a topical corticosteroid:

- apply your emollient first and ideally wait around 30 minutes until the emollient has soaked into your skin, or apply the corticosteroid at a different time of day (such as at night)

- apply the recommended amount of the topical corticosteroid to the affected area

- continue to use it until 48 hours after the flare-up has cleared so the inflammation under the skin surface is treated

Occasionally, your doctor may suggest using a topical corticosteroid less frequently, but over a longer period of time. This is designed to help prevent flare-ups.

This is sometimes called weekend treatment, where a person who has already gained control of their eczema uses the topical corticosteroid every weekend on the trouble sites to prevent them becoming active again.

Side effects

Topical corticosteroids may cause a mild stinging sensation for less than a minute as you apply them.

In rare cases, they may also cause:

- thinning of the skin – especially if the strong steroids are used in the wrong places, such as the face, for too long (for example, several weeks)

- changes in skin colour – usually, skin lightening after many months of using very strong steroids, but most lightening after eczema is a “footprint” of old inflammation and nothing to do with treatments

- acne (spots) – especially when used on the face in teenagers

- increased hair growth

Most of these side effects will improve once treatment stops.

Your risk of side effects may be increased if you use a strong topical corticosteroid:

- for many months

- in sensitive areas such as the face, armpits or groin

- in large amounts

You should be prescribed the weakest effective treatment to control your symptoms.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are a type of medicine that block the effects of a substance in the blood called histamine.

They can help relieve the itching associated with atopic eczema.

They can either be sedating, which cause drowsiness, or non-sedating.

If you have severe itching, a GP may suggest trying a non-sedating antihistamine.

If itching during a flare-up affects your sleep, a GP may suggest taking a sedating antihistamine.

Sedating antihistamines can cause drowsiness into the following day, so it may be helpful to let your child’s school know they may not be as alert as normal.

Bandages and wet wraps

In some cases, a GP may prescribe medicated bandages, clothing or wet wraps to wear over areas of skin affected by eczema.

These can either be used over emollients or with topical corticosteroids to prevent scratching, allow the skin underneath to heal, and stop the skin drying out.

Corticosteroid tablets

Corticosteroid tablets are rarely used to treat atopic eczema nowadays, but may occasionally be prescribed for short periods of 5 to 7 days to help bring particularly severe flare-ups under control.

Longer courses of treatment are generally avoided because of the risk of potentially serious side effects.

If a GP thinks your condition may be severe enough to benefit from repeated or prolonged treatment with corticosteroid tablets, they’ll probably refer you to a specialist.

Seeing a specialist

In some cases, a GP may refer you to a specialist in treating skin conditions (dermatologist).

You may be referred if:

- a GP is not sure what type of eczema you have

- normal treatment is not controlling your eczema

- your eczema is affecting your daily life

- it’s not clear what’s causing it

A dermatologist may be able to offer the following:

- allergy testing

- a thorough review of your existing treatment – to make sure you’re using enough of the right things at the right times

- topical calcineurin inhibitors – creams and ointments that suppress your immune system, such as pimecrolimus and tacrolimus

- very strong topical corticosteroids

- bandages or wet wraps

- phototherapy – ultraviolet (UV) light that reduces inflammation

- immunosuppressant tablets – to suppress your immune system, such as azathioprine, ciclosporin and methotrexate

- alitretinoin – medicine to treat severe eczema affecting the hands in adults

- dupilumab – a medicine for adults with moderate to severe eczema that may be tried when other treatments have not worked

A dermatologist may also offer additional support to help you use your treatments correctly, such as demonstrations from specialist nurses, and they may be able to refer you for psychological support if you feel you need it.

Complementary therapies

Some people may find complementary therapies such as herbal remedies helpful in treating their eczema, but there’s little evidence to show these remedies are effective.

If you’re thinking about using a complementary therapy, speak to a GP first to ensure the therapy is safe for you to use.

Make sure you continue to use other treatments a GP has prescribed.

Bacterial skin infections

As atopic eczema can cause your skin to become cracked and broken, there’s a risk of the skin becoming infected with bacteria. The risk is higher if you scratch your eczema or do not use your treatments correctly.

Signs of a bacterial infection can include:

- fluid oozing from the skin

- a yellow crust on the skin surface

- small yellowish-white spots appearing in the eczema

- the skin becoming swollen and sore

- feeling hot and shivery and generally feeling unwell

Your normal symptoms may also get rapidly worse and your eczema may not respond to your regular treatments.

You should see a doctor as soon as possible if you think your or your child’s skin may have become infected.

They’ll usually prescribe antibiotics to treat the infection, as well as making sure the skin inflammation that led to the infection is well controlled.

Speak to a GP if these do not help or your symptoms get worse.

Once your infection has cleared, a GP will prescribe new supplies of any creams and ointments you’re using to avoid contamination. Old treatments should be disposed of.

Viral skin infections

It’s also possible for eczema to become infected with the herpes simplex virus, which normally causes cold sores. This can develop into a serious condition called eczema herpeticum.

Symptoms of eczema herpeticum include:

- areas of painful eczema that quickly get worse

- groups of fluid-filled blisters that break open and leave small, shallow open sores on the skin

- feeling hot and shivery and generally feeling unwell, in some cases

Contact a doctor immediately if you suspect eczema herpeticum. If you cannot contact a GP, call NHS 111 or go to your nearest hospital.

If you’re diagnosed with eczema herpeticum, you’ll be given an antiviral medicine called aciclovir.

Psychological effects

As well as affecting you physically, atopic eczema may also affect you psychologically.

Preschool children with atopic eczema may be more likely to have behavioural problems such as hyperactivity than children who do not have the condition. They’re also more likely to be more dependent on their parents.

Bullying

Schoolchildren may experience teasing or bullying if they have atopic eczema. Any kind of bullying can be traumatic and difficult for a child to deal with.

Your child may become quiet and withdrawn. Explain the situation to your child’s teacher and encourage your child to tell you how they’re feeling.

The National Eczema Society provides information about regional support groups, where you may be able to meet other people living with atopic eczema.

Problems sleeping

Sleep-related problems are common among people with eczema.

A lack of sleep may affect mood and behaviour. It may also make it more difficult to concentrate at school or work.

If your child has problems sleeping because of their eczema, they may fall behind with their schoolwork. It might help to let their teacher know about their condition so it can be taken into consideration.

During a severe eczema flare-up, your child may need time off from school. This may also affect their ability to keep up with their studies.

Self-confidence

Atopic eczema can affect the self-confidence of both adults and children. Children may find it particularly difficult to deal with their condition, which may lead to them having a poor self-image.

If your child is severely lacking in confidence, it may affect their ability to develop social skills. Support and encouragement will help boost your child’s self-confidence and give them a more positive attitude about their appearance.

Speak to a GP if you’re concerned your child’s eczema is severely affecting their confidence. They may benefit from specialist psychological support.